What is inquiry-based learning? Benefits & examples

Inquiry-based learning is an instructional method that prioritises student-led discussion and discovery.

What is inquiry-based learning?

Have you ever posed a question to a group of students and been met with crickets? Even worse, downward gazes, uncomfortable shifting, and the gnawing feeling that you’ve totally lost them? You may be asking the wrong questions.

With inquiry based learning, the students’ interests and curiosity are put front and centre. By allowing them to drive the conversation forward based on what they want to know, they’ll be automatically invested in discovering more. This encourages critical thinking, evidence-based reasoning, and creative problem solving.

Types of inquiry-based learning

Here are the four types of inquiry-based learning:

- Structured. The teacher leads and introduces an essential question. Related activities, resources, and assessments follow.

- Controlled. The teacher poses several questions and the students pick one to explore further.

- Guided. Students formulate their own questions and find their own resources in response to a proposed topic.

- Free. The teacher provides support as students design their own questions, choose their own resources, and customise their own assessments to demonstrate what they’ve learned.

Each of these types of inquiry-based learning is valid, but you’ll notice the structure gets looser as you go down the list. You’ll have to decide which type will work best in your classroom.

Where do I start?

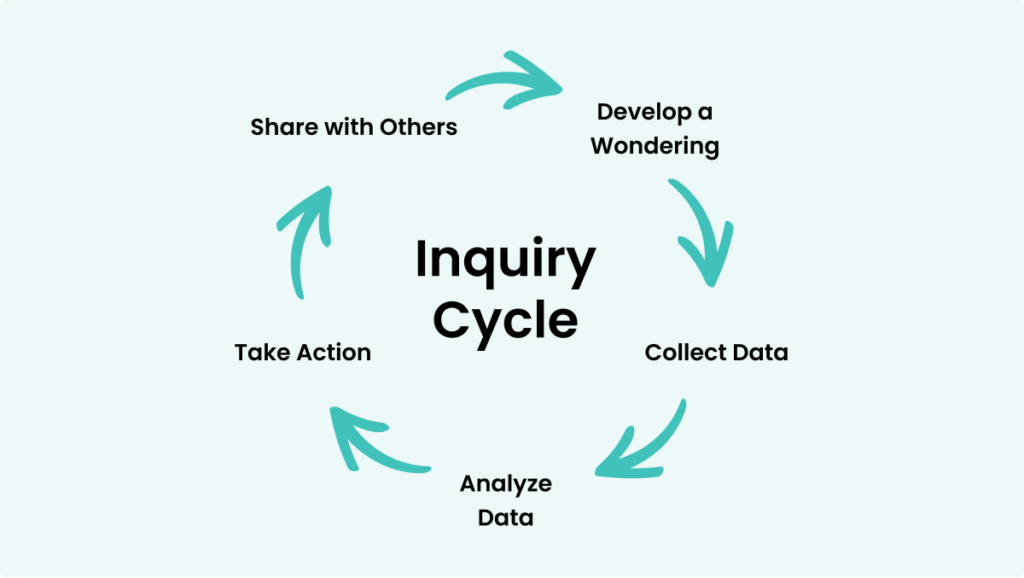

Nancy Fitchman Dana, Professor of Education in the School of Teaching and Learning at the University of Florida, Gainesville, assures us that inquiry can be broken down into the following easily digestible steps:

- Begin with a question that guides an investigation. That means you’ll want to avoid questions that can be answered with “yes” or “no”. Here we develop a wondering among the students.

- Research and collect data. This can be as big as assigning a research project or as small as making simple observations together.

- Next, it’s time to analyse data. What did they find out, and what does it all mean?

- Now take action! What can we do with this information? How will it further guide our learning and inform our knowledge?

- Share with others. Knowledge is meant to be shared!

Can I engage in inquiry outside of the classroom?

Absolutely! While it’s true that inquiry and project-based learning often go hand in hand, you can also work inquiry into other types of experiences. My personal favourite? Looking at art.

I first learned about inquiry when I was training to become a museum educator. At the museum I was hired to lead school trips, we were trained to implement an inquiry-based teaching model in the galleries when engaging students with paintings, documents, and historic artefacts.

Nicola Giardina, a leading educator in the museum field, argues that everyone should teach with art inquiry, regardless of your content area. In her book “The More We Look, The Deeper It Gets: Transforming the Curriculum Through Art” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), she asserts that art inquiry:

- Improves critical thinking skills

- Develops social-emotional skills

- Increases student engagement

- Works for all students

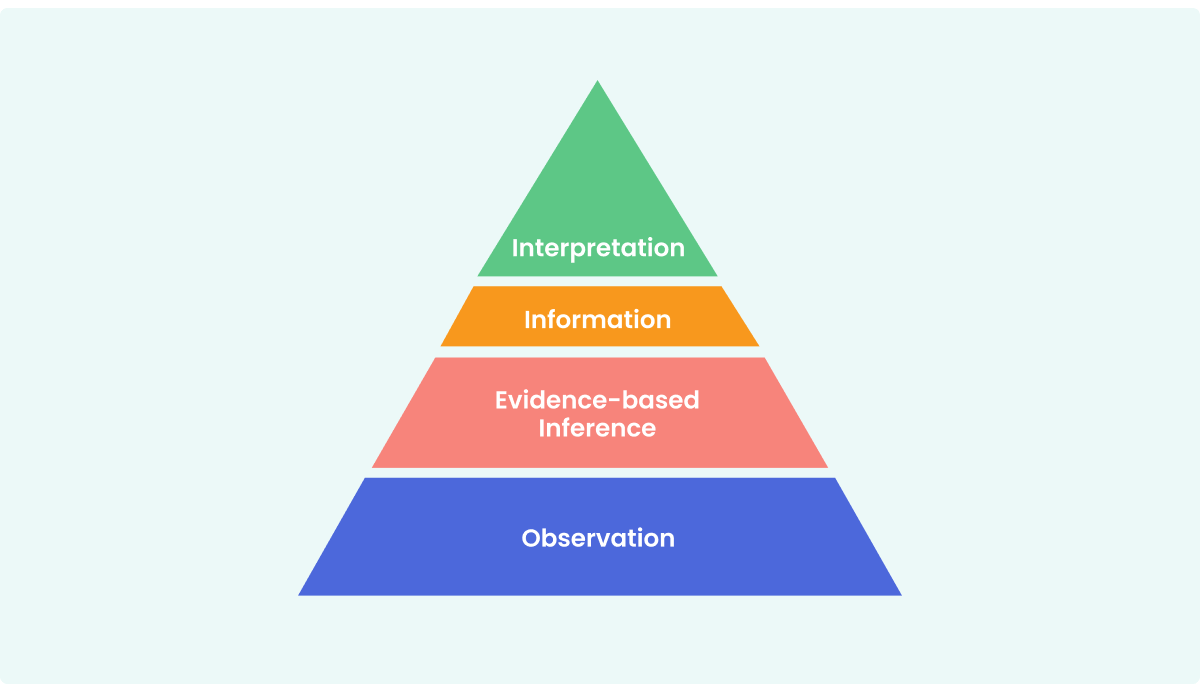

Her approach to inquiry is a pyramid rather than a cycle.

Let’s break it down further. First, imagine your students are in an art gallery, sitting in front of a large painting, and initially, they have no idea what they’re looking at. You’ll start by asking for observations. It’s as simple as asking, “What do you see?”

This type of questioning opens the door for the discussion to branch off in many ways. It’s important to remember that this will take the conversation in several directions, and that’s okay! Keep the points you want to make in the back of your mind – you’ll get there eventually.

Next is evidence-based inference. This is simply guiding your students to share what they think about what they see. For example, if in the observation phase, a student shared that “this painting is from a very long time ago”, you could ask something like, “How do you know?” They’ll be excited to share why they think that.

For a more structured approach, you can utilise a resource like See, Think, Wonder. I’ve used this successfully as both a conversation driver and as a worksheet element. This is a great tool to get your students to spend some time reflecting further on the topic at hand.

Now it’s time for information. This is where you may need to feed some hard facts into the conversation to provide context. You can provide them with the date the painting was created, or even better, ask your students to find out for themselves by reading the wall label or looking for other clues.

Finally, we come to interpretation. What’s the big idea here? I like to ask my students “What did we learn from this?” or “What is the point of this piece”? They always feel empowered sharing the discoveries they made, seemingly all on their own!

Can’t get to the gallery?

While every museum educator will implore you to take your students to museums and galleries, that’s of course not always possible. But you can always work with art and artefacts in your classroom by taking advantage of digitised collections online.

And what student doesn’t love watching videos? In our era of streaming, using video to introduce students to art and artefacts, has the added benefit of providing important contextual information so that they better understand its enduring legacy. The series Art That Changed America and Artifacts That Changed America can be used to explore key art and artefacts that have shaped U.S. history. The videos also encourage active viewing with engaging open-question prompts to drive discussions around the art or artefact that is explored.

Benefits of inquiry-based learning

According to Nancy Fitchman Dana in her book “Student Inquiry: The Basics”, when engaging in inquiry-based learning in the classroom, “Students become researchers, writers, and activists rather than passive recipients of a textbook’s content. Students take ownership of their learning; they discover that school can be a place that nurtures curiosity, inspires important questions, and produces real joy from learning.”

A bonus? Inquiry goes hand in hand with the Common Core. The Common Core Standards require students to:

- demonstrate independence;

- continuously build strong content knowledge;

- respond to the varying demands of audience, task, purpose, and discipline;

- comprehend and critique;

- value evidence;

- use technology and digital media strategically and capably; and

- come to understand other perspectives and cultures

All of which can be achieved through implementing an inquiry-based learning model in your teaching. The inquiry model also encourages higher order thinking by prompting students to go beyond the memorising of facts and figures to discover what it all really means.

Disadvantages of inquiry-based learning

What are some disadvantages of this learning model? Here are some issues you might run into (and how to combat them!)

Exam-driven curricula

An unfortunate reality of schooling today is that many teachers are assessed by how well their students perform in exams. This means that these teachers have no choice but to teach the content of the test, and to ensure their students do well on it. This doesn’t leave much room for students to explore their own interests – the guiding pillar of inquiry.

So what can you do?

Work inquiry into teaching the content! There’s no reason you can’t explore the exam content in a more meaningful way. Your students may even remember the content better for having meaningfully engaged with it. It was Benjamin Franklin who once said, “Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.”

Reluctant students

You’ll always have shy students who never raise their hands. This can be frustrating when you’re asking your students to share their observations and thoughts, and certain students refuse to participate.

So what can you do?

Foster a culture of thinking and safe sharing within your classroom. The beauty of inquiry is that when you’re asking students what they see and think, there are no wrong answers! Reinforce that mindset when guiding discussion, and your students won’t feel too intimidated to speak up.

Assessment

Traditional testing models are not compatible with an inquiry-based classroom. Educator Lee Crocket explains:

The teacher-centered paradigm of pre-preparing assessments that are designed to confirm retention of pre-determined knowledge will not work well in an inquiry setting. This model will standardize and effectively limit the levels of achievement to those that have already been decided by the teacher. When this happens, individual pathways and potential for personalized learning goals are lost.

So what can you do?

Perform checks for understanding along the way, and create unique forms of assessment that will gauge learning.

While you’re at it, make sure you’re assessing your own teaching. Here’s a helpful rubric from the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero.

Examples of inquiry-based learning

What can inquiry based learning look like, and how can you start using it in your classroom? Here are some common classroom activities that can promote inquiry:

- Object Inquiry

This might be the easiest place to begin for the inquiry newbie. I explored this earlier when discussing performing an inquiry with a painting, but inquiry can be done with any number of objects or artefacts! Pull out a replica of a strange historical artefact and your students will automatically be invested in figuring out what the heck it is.

No physical objects at your disposal? Head back to those videos I mentioned earlier! - Experimentation

I’m betting you’ve heard of the scientific method. If you thought inquiry sounded familiar, you’re not wrong. It’s not so different from inquiry, and having your students experiment in the classroom or out in the field is a great way to explore the power of inquiry. - Analyse a Book

There’s no shortage of wonderful literature available to support and enhance your curriculum. Why not allow your students to ask the questions and guide the discussion around a historical fiction novel, a sci-fi thriller, or your curriculum-mandated classical literature? As an added benefit, critically analysing a novel for accuracy will help your students develop their media literacy skills. - Gallery Walks

In a gallery walk (please see the video below), student learning is put front and centre as they display their work for their classmates. Common structures include posters, dioramas, and videos – but anything tangible they’re working on in class will do. This sharing-based model gives students the onus to explain their process while the rest of the class is given the opportunity to ask thoughtful questions. - Problem Based Learning

When you’re ready to make inquiry in your classroom to the next level, employ this student-centred approach that asks students to find a solution to an open-ended problem. PBL projects give students the opportunity to develop many important skills, and self-directed learning and inquiry is at its core.

Relevant books and resources

Helpful books:

- Fichtman, Dana Nancy, Thomas, Carol, and Boynton, Sylvia. “Inquiry: A Districtwide Approach to Staff and Student Learning” Crownpress, 2011.

- Fichtman, Dana; Yendol-Hoppey, Diane.“The Reflective Educator’s Guide to Classroom Research: Learning to Teach and Teaching to Learn Through Practitioner Inquiry” (2009) (Facilitator’s Guide Available)

- Cowhey, M. (2006). Black Ants and Buddhists: Thinking Critically and Teaching Differently in the Primary Grades. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Barron, B., Pearson, D, Schoenfeld, A. H., Stage, E. K., Zimmerman, T. D., Cervetti, G. N., & Tilson, J. L. (2008). Powerful Learning: What We Know About Teaching for Understanding. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- King, R., Erickson, C., & Sebranek, J. (2012). Inquire: A Guide to 21st Century Learning. Burlington, WI: Thoughtful Learning.

- Wolk, S. (2008). “School as Inquiry.” Phi Delta Kappan, 90(2), 115–122.

- Giardina, N. (2018). The More We Look, the Deeper It Gets: Transforming the Curriculum Through Art. United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Lee, V. S., Greene, D. B., Odom, J., Schechter, E., & Slatta, R. W. (2004). What is inquiry guided learning. In V. S. Lee (Ed.), Teaching and learning through inquiry: A guidebook for institutions and instructors (pp. 3-15). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Mackenzie, Trevor and Bathurst-Hunt, Elementary Edition: Nurturing the Dreams, Wonders, and Curiosities of Our Youngest Learners. Elevate Books Edu, 2019.

- MacKenzie, Trevor. Dive Into Inquiry. United States, Elevate Books Edu, 2019.

Helpful sites and downloadables:

- Learning by Inquiry

- Inquiry Resources

- Chalk Talk

- See / Think / Wonder

- I Used to Think… Now I think…

- What Makes You Say That? (Adapted)

- Pocket Guide to Probing Questions – School Reform Initiative

- PZ’s Thinking Routines Toolbox | Project Zero

- Cultures of Thinking Student Recording Sheets | Project Zero